This is my translation of my original article in Hungarian

These photos bear witness to a rather unusual view of life. They were taken on family holidays in the 1960s and 1970s, in Belgium, Italy, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, the GDR and the USSR. Viewed from Hungary, this family must have been especially lucky to have travelled so much.

But my family is from Wales, and my maternal grandparents were members of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) for over two decades, which is why they travelled east, not just out of curiosity or a desire for adventure, but also because of an old-fashioned ideological conviction. In terms of what they saw, the photos speak for themselves.

The path in life taken by John and Lorraine Griffiths was not particularly unique. Together with countless other young university students in the 1930s, they joined the CPGB, probably one of the very few occasions that an exceptionally rare cross-section of British society came together in one place: first generation intellectuals like them, the traditional elite and their offspring (such as the Cambridge Five), and members of the industrial working class.

What attracted them in the first place? In the 1930s, many people hoped and believed that a new world would be born. The stakes were high: either death by swastika, or the future of humanity. The fact that the Soviet Union was momentarily able to present itself as the embodiment of this new world explains, in part, the popularity of the British Communist Party.

Many autobiographies of British Communists emphasise the fact that in the 1930s, and during the Spanish Civil War, joining the Party was seen as simply cool. What my grandmother particularly liked was that in Party circles, she could, as a woman, have short hair, wear trousers, and talk about meaningful things, all while chain-smoking, of course.

In other words, for those young people dissatisfied with the injustice and cynicism of capitalism, the Party provided a sort of intellectual home in a country where it was relatively easy not only to join the Party, but also to leave it. But one didn’t discuss Party membership with just anybody. This information was often kept secret, especially from the bosses. My Mum remembers that when she was small, she only got into serious trouble at home when she stuck the colourful Party membership stamps on the wall for fun.

In its heyday towards the end of the Second World War, the CPGB had 60,000 members, and at the 1945 national elections, when the wartime leader Winston Churchill was kicked out, the Party won 100,000 votes. After the war however, Party members ended up on various blacklists, and membership numbers slowly began to dwindle. 1956 and the Hungarian uprising was also a watershed point in the history of the CPGB: it functioned as the opposite of a membership drive. Following the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian revolt, one third of the CPGB members left overnight – including my grandparents. Those who stayed were nicknamed ‘tankies’, in other words those who solve all problems with tanks. This slang is still in use on the British left.

Not long ago, I read an unbelievably contrived and positive account by a Canadian fisherman trade unionist of his local CP-sponsored 1952 visit to the Soviet Union and China. On his travels, he was able to marvel at such unheard of and unsurpassable socialist achievements such as rye bread or opera performances. In contrast, my grandparents were perfectly aware of the fact that after 1956 and during the Cold War, the good things in life were not the sole preserve of the fraternal countries. They were curious about the socialist world, but as ‘fellow travellers,’ had a certain critical disposition. It was in this spirit that they travelled east in the 1960s and 1970s.

Their photos oscillate somewhere between two poles: on the first two trips, we see a family on vacation, and in the second two series of pictures, they are on a distinctly political visit. The travels begin in Western Europe with a 1966 trip to Belgium (Brussels) and Italy (Venice): classic family summer holiday snaps.

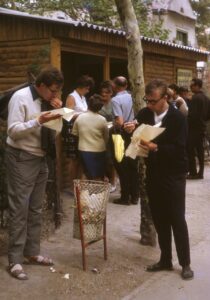

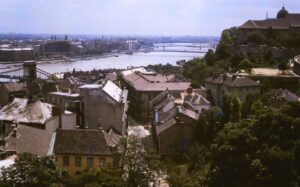

Six stubborn people travelled together in a Morris Oxford with a tent whose frame was produced in the GDR, while its canvas was made in Hungary. In other words, they didn’t fit. Next up is a holiday in the summer of 1968, first to Czechoslovakia (Karlovy Vary and Prague), then to Hungary (Balaton and Budapest), replete with proper tourist vibes, people taking a break. Although there were firms in Britain at the time that organised visits to socialist countries on ideological grounds, nobody in the family can remember which travel bureau they went with.

In the next two series, the comradely spirit is much more to the fore. My grandmother had graduated in French and German at Cardiff University in the 1930s. And later on, when she was training to become a German teacher, she visited East Germany (Erfurt and Berlin) in 1970 with my grandfather. Here we see, as well as the landscape pictures, the Ernst Thälmann Pioneer Organisation May Day parade, kindergarten children attending something that resembles a Party-led discussion, and a Freie Deutsche Jugend (Free German Youth, FDJ) conference, featuring the slogan: “On the side of the comrades – performing great achievements in honour of the GDR!” No hapless tourists ended up here: everything in these photos was orchestrated by an organisation closely tied to the Party.

And finally in 1973, the year I was born, my grandparents went on a cruise down the Volga. These photos document the sites and icons of the Communist movement – monuments to the decisive Battle of Stalingrad, the Motherland Calls statue in Mamayev Kurgan park, and the Aurora battleship in Leningrad – as well as fine portraits of the Volga itself, children playing with a dog on the riverbank, an elderly man with his weighing scale, and weddings parties with cheerful bridesmaids.

What I like most about these photos is that there is only one of each. Since film and photo development were also expensive in the West, you only pressed the button to take the picture once the scene was composed, and everything was (hopefully) in its place. These slides were taken on Ilford film, probably with a Soviet or East German camera. For sure, certain Eastern brands were also in demand in the West, such as Soviet Sekonda watches and Zenit cameras, or East German Zeiss cameras and binoculars.

But apart from the export consumer goods – and the fact that it was of course much cheaper and more exciting to go on holiday in the East – two things impressed Western left-wingers back then. First of all, these societies had made chronic unemployment a thing of the past, albeit in a particularly clumsy and stupid way. Second, the occupied European states remained European societies where European people lived, and for the curious Westerner who had the means and passport with which to travel, a familiar yet unknown world was waiting to be encountered.

My experience in 1995 was somewhat similar when I first came to Hungary to teach English for three months, and stayed. It’s already 18 years that I call Budapest my home, but that’s a different story.